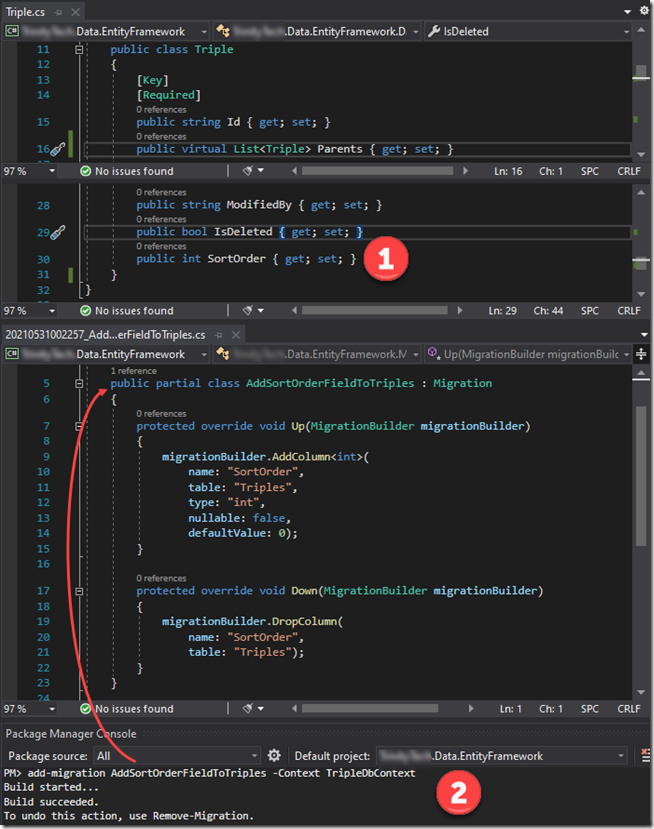

1. Make the change to the class, e.g., below I added SortOrder property

2. Open Package Manager Console and type:

PM> add-migration AddSortOrderFieldToTriples – Context TripleDbContext

This will result in the auto-generation of the AddSortOrderFieldToTriples class. Note below that since my TripleDbContext resides in a separate assembly (not the web application) I have to set the “Default Project” to its location. Since there are two context (ApplicationDbContext and TripleDbContext) in that assembly I have to also provide the –Context parameter.

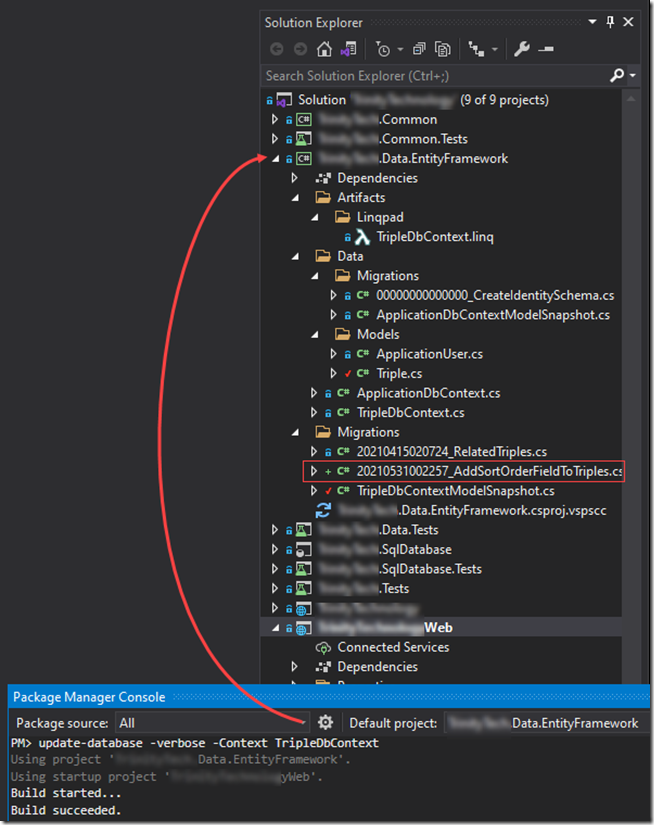

Once the classes have been updated you will type in the following:

PM> update-database –verbose –Context TripleDbContext

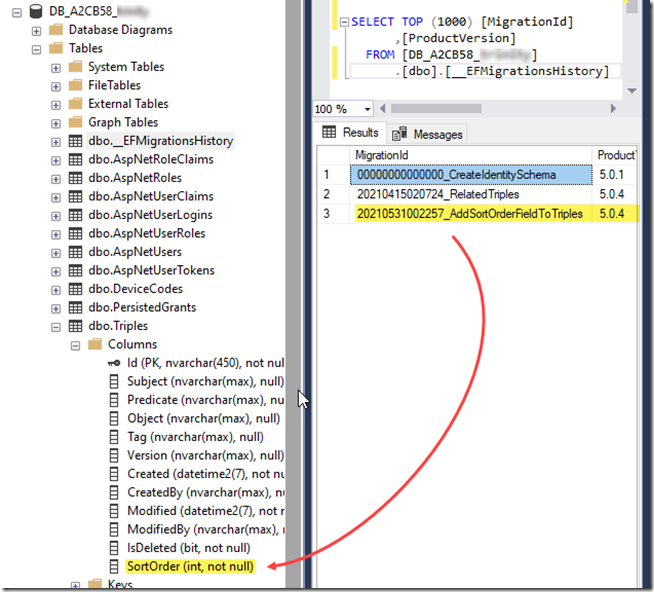

This will apply the change to the database table as shown below:

The process is pretty much straight forward with some caveats that I’ll explain below.

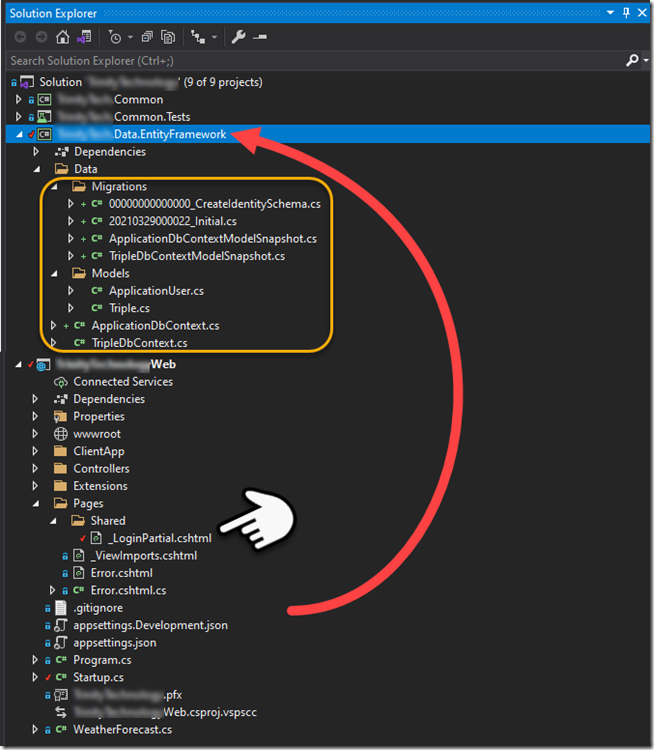

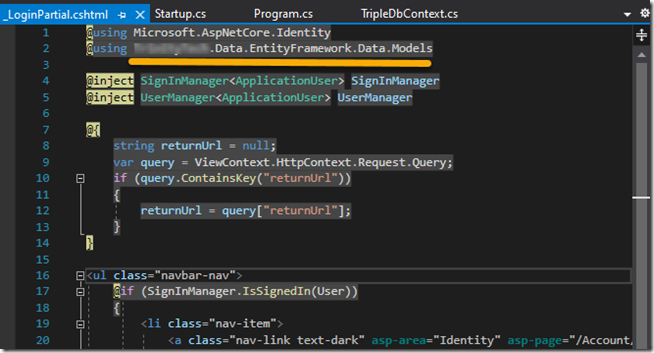

First I moved the Data/Migrations and Models folder out of my web app into to my new project (figure 1). I got an unexpected compile error - it was a rather obscure error from the _LoginPartial.cshtml.gs.s file – which is the compiled file. To resolve this I had to update the _LoginPartial.cshtml manually since intellisense was not working in this file (figure 2). Once I did that, and updated namespaces for the existing ApplicationUser references, my web app was compiling and running again.

Figure 1

Figure 2

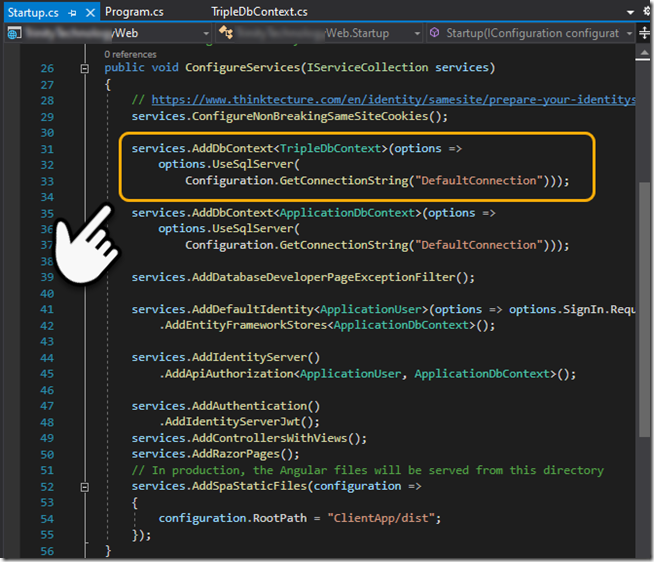

I created my new TripleDbContext as well as the Triple table (see figure 1). I then added the code pointed to below so that my new TripleDbContext will have a connection string when needed.

Figure 3

If you don’t have the dotnet –ef tool installed you can go to the root of your web app [command prompt] and type the following:

dotnet tool install --global dotnet-ef

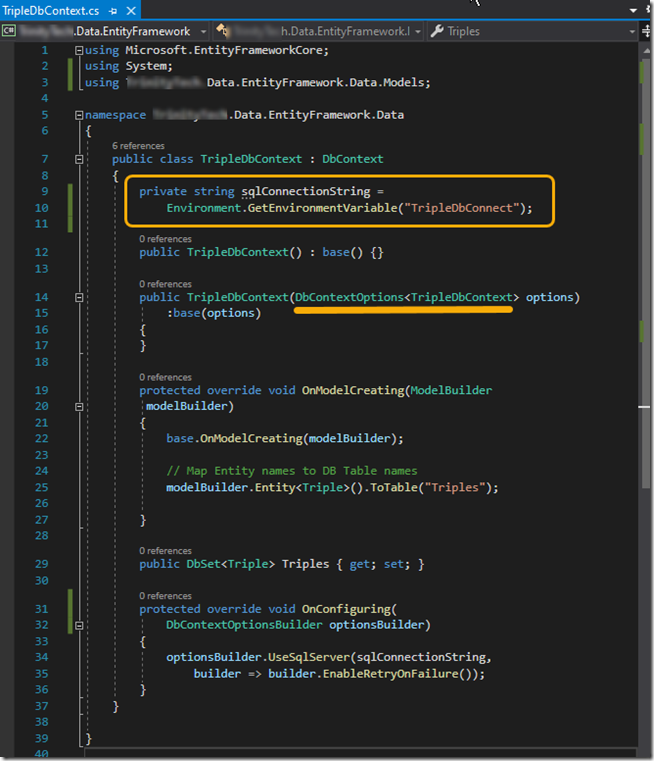

After installed you’ll need need to switch to the “project that contains your xxxDbContext” and use the following command line. Since we have more than one context, e.g., ApplicationDbContext (security) and TripleDbContext (new) we have to provide the –context or it will complain, likewise we have to specify the DbContextOptions<TripleDbContext> in the constructor for options (see figure 4).

dotnet ef migrations add "Initial" -o "Data/Migrations" --context TripleDbContext

dotnet ef database update --context TripleDbContext

Note that I provide the connection string for the OnConfiguring() function from the environment – this will only be needed when configuring the database, e.g., doing the two commands above.

Figure 4

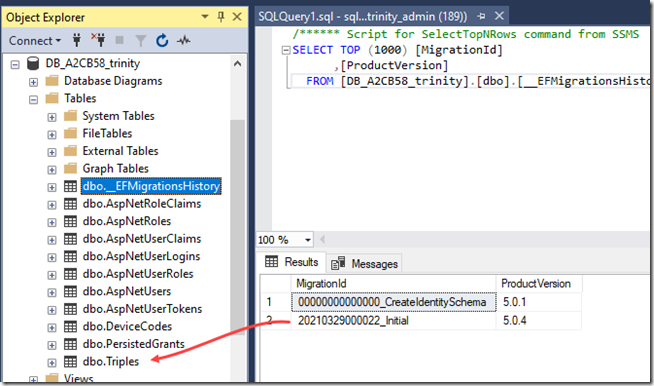

With that you’ll find your database has the new database table.

Figure 5

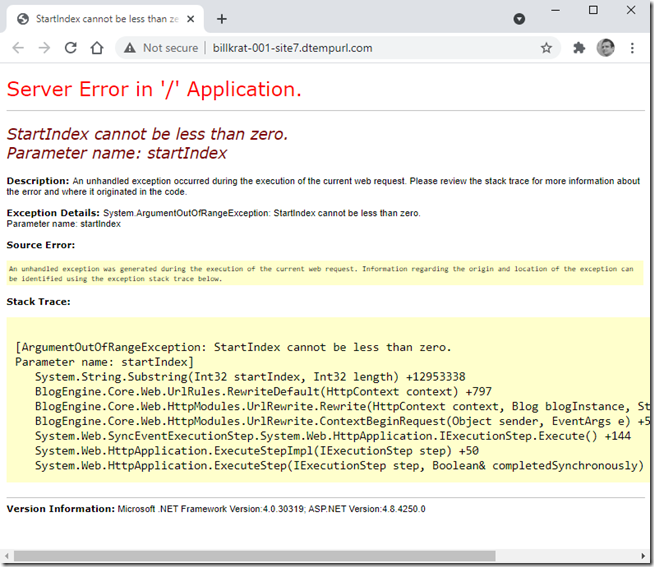

Behind the scenes the “default.aspx” is being searched for; if you put a /default.aspx at the end of the URL you will find that the page will load.

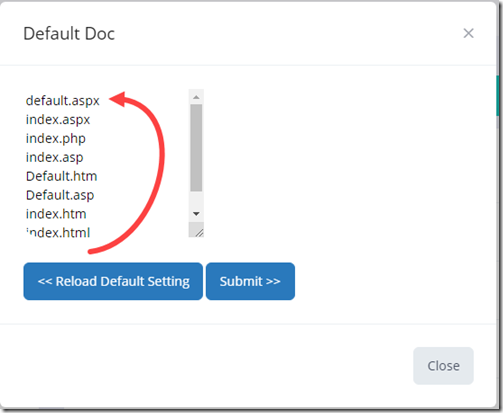

The fix is to go into the site settings and set the “Default Doc” to default.aspx. In my case I had to manually cut the default.aspx from the last position (figure 2) and then paste it above index.aspx. Once I did this the site started working as expected

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

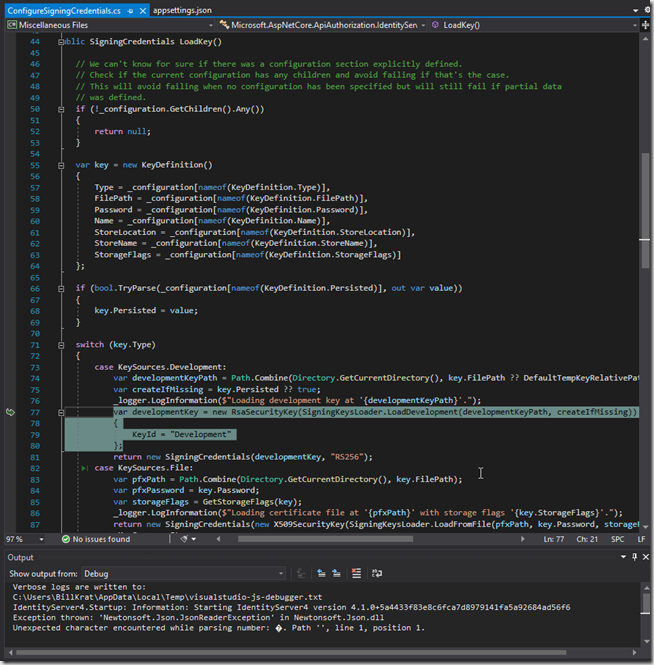

IdentityServer4.Startup: Information: Starting IdentityServer4 version 4.1.0+5a4433f83e8c6fca7d8979141fa5a92684ad56f6

Exception thrown: 'Newtonsoft.Json.JsonReaderException' in Newtonsoft.Json.dll

Unexpected character encountered while parsing number: �. Path '', line 1, position 1.

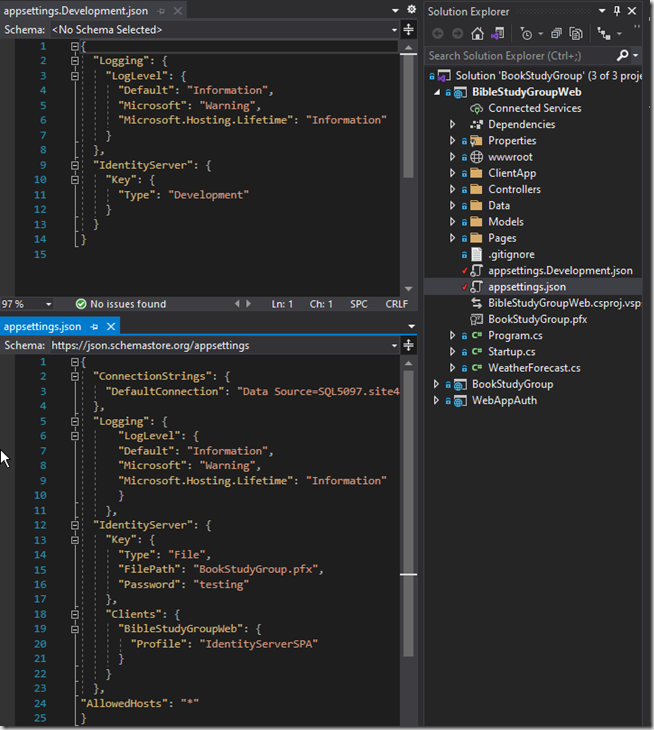

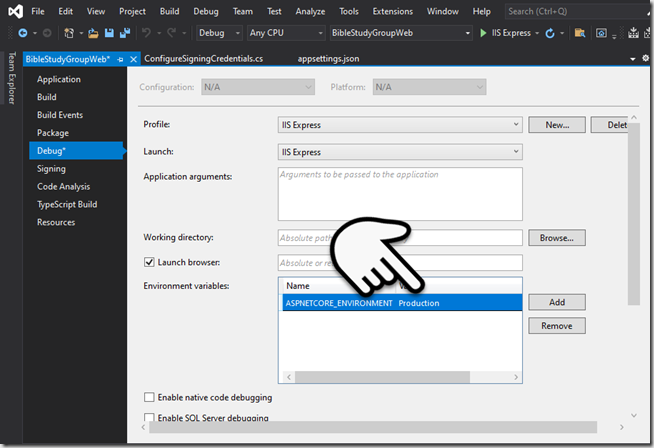

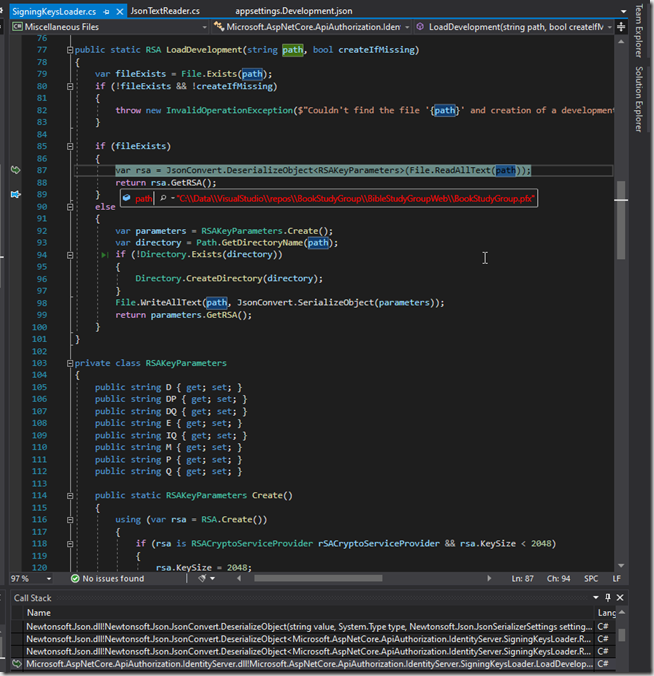

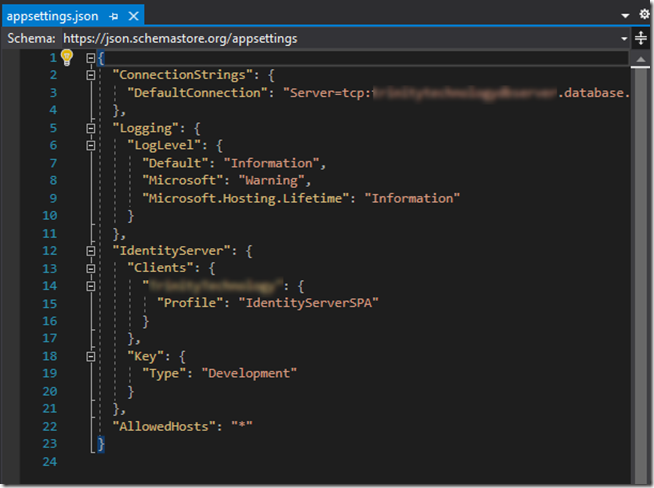

You’ll see this error if you are configured with an IdentityServer type=File (figure 1) and your environment is setup to run in “Development”; the fix is to set the ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT=Production (figure 2). Likewise you can leave the setting at “Development” but will have to copy the appsettings.json “IdentityServer” segment to the appsettings.Development.json file (removing the Key type = Development).

In figure 3 and 4 you can see that it gets confused thinking it is in Development expecting JsonConvert to deserialize the contents when in fact the path is our .pfx file. By setting it to Production it ignores the appsettings.Development.json (more closely emulating a production deployed environment which can aid with debugging issues).

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

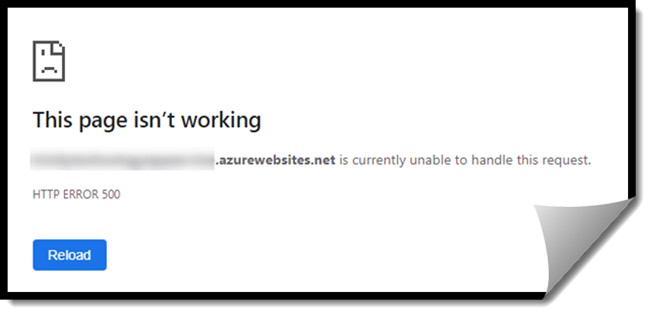

500 error when deployed

Object reference not set to an instance of an object.

Problem Id:

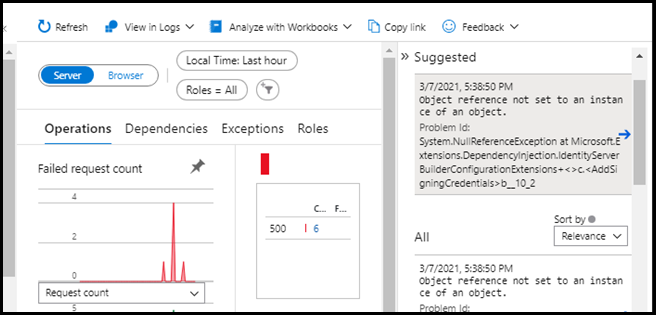

System.NullReferenceException at Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection.IdentityServerBuilderConfigurationExtensions+<>c.<AddSigningCredentials>b__10_2

This can be tough to diagnose if you are not deployed to Azure [with application insights enabled]. With app insights the message is not real helpful, but a clue lies in the “identityServerBuildConfigurationExtension”

To verify the issue is with identity server configuration you can update the appsettings.json as shown below and redeploy. If the site comes up but you can’t access the default “Fetch data” (see image) then this is the source of your problem; identity server configuration.

in the appsettings.json add the following section:

"Key": {

"Type": "Development"

}

The application will now run [in azure], however this configuration should not be used in a production environment. The following link provides the steps [links] to “Deploy to Azure App Service”

Note: this fix will allow your site to work if you are deploying to Azure [because it is a secure site using https], however if you are trying to deploy to an ISP using http you'll have some more work because http causes error when deployed

16. January 2020

Admin

VSCode

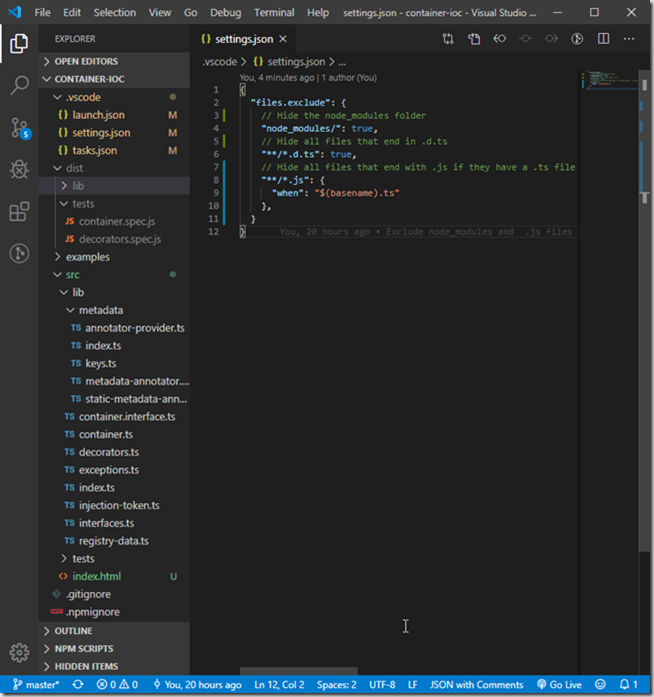

1. Create a settings.json file under the .vscode folder if it does not exist.

2. Add the following settings and save

{

"files.exclude": {

// Hide the node_modules folder

"node_modules/": true,

// Hide all files that end in .d.ts

"**/*.d.ts": true,

// Hide all files that end with .js if they have a .ts file

"**/*.js": {

"when": "$(basename).ts"

},

}

}

23. November 2019

Admin

VS Code

.vscode.zip (1.91 kb)

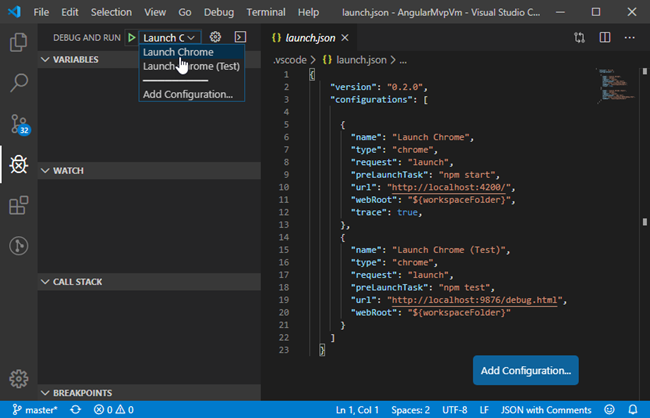

Figure 1. Launch debugger in Chrome

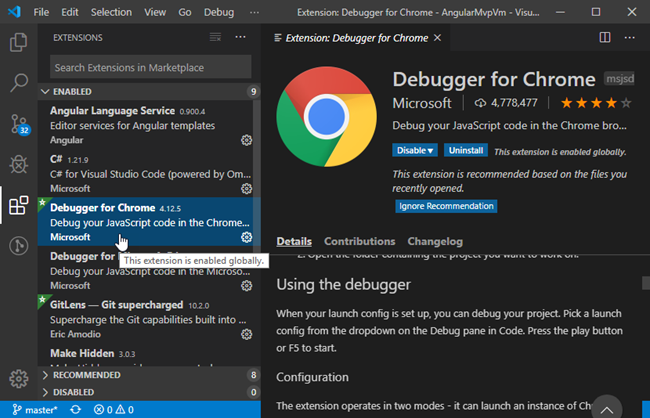

- Ensure Debugger for Chrome extension is installed (figure 2)

- In .vscode folder add launch (figure 3) and tasks (figure 4) json files

- From VS Code debug select Launch Chrome or Launch Chrome (Test)

Figure 2. Visual Studio Code extension for Debugger for Chrome

{

"version": "0.2.0",

"configurations": [

{

"name": "Launch Chrome",

"type": "chrome",

"request": "launch",

"preLaunchTask": "npm start",

"url": "http://localhost:4200/",

"webRoot": "${workspaceFolder}",

"trace": true,

},

{

"name": "Launch Chrome (Test)",

"type": "chrome",

"request": "launch",

"preLaunchTask": "npm test",

"url": "http://localhost:9876/debug.html",

"webRoot": "${workspaceFolder}"

}

]

}

Figure 3. launch.json file

{

"version": "2.0.0",

"tasks": [

{

"label": "npm start",

"type": "npm",

"script": "start",

"isBackground": true,

"group": {

"kind": "build",

"isDefault": true

},

"problemMatcher": {

"pattern": "$tsc",

"background": {

"beginsPattern": {

"regexp": "(.*?)"

},

"endsPattern": {

"regexp": "Compiled |compile."

}

}

}

},

{

"label": "npm test",

"type": "npm",

"script": "test",

"problemMatcher": [],

"group": {

"kind": "test",

"isDefault": true

}

}

]

}

Figure 4.

tasks.json file